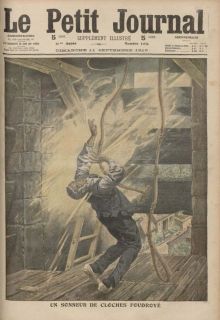

Sept. 11, 1910 issue of Le Petit Journal (via YouScribe.com) - Autor:

On Sunday, Reddit user jspindle shared this frightening piece of trivia with the Today I Learned (TIL) community: “TIL that so many people died by ringing church bells in storms, due to the belief that it would disperse thunder, that the practice was banned by the Parlement of Paris.”

Though jspindle’s fact of the day didn’t come from the most reputable of historical sources, it turns out this one is sadly true.

Introducing a new contender for the worst job in history: bell-ringer—during a lightning storm.

When you learned about the invention of the lightning rod in grade school, you probably heard something like this: Ben Franklin takes a kite and a house key into a thunderstorm and “discovers” electricity, followed naturally by a thank-you card from the rest of the world and a government-mandated lightning rod on every tall building. Right?

What they didn’t tell you is that when Franklin debuted his life-saving invention, it faced some stiff intellectual competition: hundreds of years of religious superstition.

In the centuries leading up to Franklin’s lightning rod, much of the Western world believed there was a definite connection between God and every instance of lightning.

Where does this idea come from? If your first thought was “Zeus,” you’re actually not too far off.

In an 1887 issue of Popular Science Monthly, Andrew White details how early Christians probably adopted the idea of a lightning bolt-slinging higher power from the Roman god Jupiter.

According to White, the belief that lightning was associated with divine judgment spread, in part due to a 13th-century monk named Cæsar of Heisterbach, whose writings included many lightning-infused religious parables like:

It’s easy to see why religious figures were especially inclined to imbue lightning with divine significance—because churches were disproportionately affected by it.

As the tallest buildings in the area, large houses of worship with steeples and spires were more likely to be struck by lightning than other, smaller buildings during storms.

The odds of getting “struck by lightning” may be a cliché means of comparison to say that something is unlikely, but for many churches, these odds weren’t trivial at all.

As Seymour Stanton Block notes, the 340-foot-tall bell tower of St. Mark’s cathedral in Venice was struck by lightning in 1388, 1417, 1489, 1548, 1565, 1658, and 1745. (Oh, and two more times in 1761 and 1762.)

So, finding a way to prevent lightning damage was more important to the clergy than perhaps any other group at the time.

Unfortunately, the church’s response to this problem was one of the worst ideas they could’ve come up with. Michael Brien Schiffer explains, in his book Draw the Lightning Down:

“In view of this constant threat, clergy and church elders over the centuries had arrived at a technological solution to ward off lightning. Believing that thunderstorms were caused by evil forces or a displeased deity, they involved the ringing of bells as a protection.”

Yes, their answer to the problem of lightning was to have a human being, in a storm, climb up to the top of a tall tower to ring a church bell made of a highly conductive metal. (Using a rope dampened by the rain.)

What could go wrong?

People certainly believed in the power of church bells to keep bad weather at bay.

According to Philip Dray, in his book Stealing God’s Thunder, many bells carried inscriptions bragging about their power to dispel lightning. The engraving on one German bell reads, “Fulgur arcens et dæmones malignos” (or “Warding off lightning and evil spirits”), while a French bell claims, “Ego sum qui dissipo tonitrua” (or “It is I who dissipate the thunders”). Other bells simply bear the phrase “Fulgura flango” (or “I subdue the thunderbolt”).

In addition to the inscriptions, bells often received special lightning-related blessings. In an 1855 essay, French physicist François Arago quotes a particularly colorful prayer from a bell-blessing ceremony:

“May the sound of this bell put to flight the fiery darts of the enemy of man; the ravages of thunder and lightning, the rapid fall of stones, the disasters of tempests …”

Even supposed men of “reason” like René Descartes and Francis Bacon, who weren’t convinced by the church’s superstitions, agreed with the use of bell-ringing as a valid storm repellant. As Dray explains, they thought the acoustical disturbance of ringing a large bell would create “some concussive energy that deterred lightning bursts.”

(Because when you play rock-paper-sound-lightning, sound always beats lightning.)

Thus, this half-baked bit of medieval “church science” became a widespread practice across Europe, and the churches’ poor, designated bell-ringers died all the time.

As proof, Dray offers a widely cited 1784 German publication titled “A Proof That the Ringing of Bells During Thunderstorms May Be More Dangerous Than Useful.”

According to Dray, the text gives a tally of “121 bell-ringers killed” by lightning from 1750–1783, including one storm that took out “seven people instantaneously,” three of them bell-ringers.*

In Jeffery Rosenfeld’s book Eye of the Storm, the author describes a 1718 storm over Brittany in northwest France, in which “two bell ringers died and 24 different churches were struck by lightning.”

And Arago gives a long list of bell-ringers fatally struck by lightning throughout France—in Sarliac, Saint-Robert, Cornille, and Dauphiné.

You would think that a consistent trend of bell-ringers dying from getting struck by lightning would be sufficient proof that bell-ringing does not, in fact, ward off lightning. So why did the tradition live on?

Schiffer’s response:

“… in explaining why lightning struck a church, parishioners could rationalize that the bell ringer was just a little tardy in getting started or had played the wrong tune. Alternatively, had the bells not been rung, the church would have suffered damage far greater.”

As Luc Rombouts points out in Singing Bronze: A History of Carillon Music, the belief in the logic of bell-ringing was so strong that there are “stories of residents of neighboring towns competing to force the thunderstorms to the other village via their respective bells.”

He also mentions that if lightning did strike a church where a bell-ringer was actively sounding the bell and the poor bell-ringer somehow managed to survive, it probably wouldn’t cause people to question the logic of the practice—but it could be “cited as a reason not to pay the bell-ringers.”

Yet another reason why 18th-century bell-ringer is one of the worst jobs in history.

When your elementary school teacher shared the story of Benjamin Franklin and the lightning rod, do you remember the ending? You know, the protracted final chapter in which Franklin responds to religious objections from preachers opposed to scientific meddling with God’s meteorological will?

Lightning, of course, was a sensitive subject at the time, so Franklin anticipated religious resistance when he wrote about his new invention that sought to tame it.

In a 1753 issue of Poor Richard’s Almanack, he begins his famous explanation of how to protect houses from lightning with this line: “It has pleased God in his Goodness to Mankind, at length to discover to them the Means of securing their Habitations and other Buildings from Mischief by Thunder and Lightning.”

Or, in other words: God wasn’t casting lightning bolts in holy judgment. If the Almighty was responsible for anything lightning-related, it was giving humans the ability to protect themselves from the phenomenon.

Back in Europe, this opposition to letting science mess with the Lord’s lightning continued well after Franklin proposed a viable solution with his lightning rod—but scientists eventually helped the church see the light.

In the essay “Identity, Bells, and the Nineteenth-Century French Village,” Alain Corbin notes that “an episcopal statute of 1768 banned bell ringing during thunderstorms” in one French diocese. Similar local laws followed, leading up to the 1784 nationwide prohibition of bell-ringing during thunderstorms—ratified by the Parlement de Paris in 1787.

Last page of the (increasingly lengthy and historically complicated) children’s book on the lightning rod, right?

Unfortunately, unlike the poor bell-ringers, the absurd practice did not die right away. As historian Eugen Weber explains, despite the Parlement’s ban, local government officials in France were reluctant to enforce it.

“Throughout Mâconnais and Bourbonnais, as in other regions, mayors hesitated to enforce the official injunctions against bell ringing, well knowing that their people would turn against them,” he writes.

Dray supports this claim, adding that “as late as 1824 four new bells baptized against lightning were raised into place at the Cathedral of Versailles.”

But some churches were open to leaving the custom behind.

“Clergy and church elders doubtless regretted the loss of life occasioned by the bell-ringing ritual; perhaps that is why some churches were receptive to experimenting with alternative technologies,” Schiffer notes.

Remember St. Mark’s Basilica, that Venice cathedral that was struck by lightning nine times? They installed a rod in 1766, and were free from lightning damage ever since.

By 1768, Franklin’s invention had been installed successfully in enough buildings to give his “heretical rod” more credibility. As he writes in a letter to Harvard professor John Winthrop, lightning rods offered “much better conductors” than a church bell’s hemp ropes—although he notes with subtle resentment that church vestries were “not well acquainted with these facts.”

These days, most of the world’s largest bells are swung via electric motors, but the bell-ringers that haven’t been replaced by machines are unlikely to die by electrocution.

Their salvation from lightning is due to both the gradual disappearance of mid-thunderstorm ringing rituals and the broader implementation of lightning rods and lightning-safe architecture in churches.

Of course, for those brave enough to carry on the bell-ringing tradition, the job is not without hazards.

In a 1990 study on injuries sustained by England bell-ringers, researchers found that the most common workplace injury was arthritis—though the most serious was still death.

Of the seven on-the-job fatalities they reported, however, not one was attributed to lightning. Two were suicides, and the other five were—in no particular order—”broken stay,” “fell from bell frame,” “fell into bells,” “rope caught under foot,” and “hit head on box.” (Other frightening injuries include four “near hangings” and two tooth-extractions due to “rope flick[ing] across mouth.”)

In a comment on the original Today I Learned post, user jspindle explains how they came across the strange fact about the deaths of bell-ringers in the first place. “[I] recently discovered my mother was a campanologist for years,” jspindle shares, “and while Googling bell-ringing I came across this gem.”

For those unfamiliar with the term “campanologist,” it’s someone trained in the art of musical bell-ringing. Perhaps now redditor jspindle will appreciate that their mother survived one of history’s most dangerous jobs.

|

||

© UpVoted (2015) © Campaners de la Catedral de València (2024) campaners@hotmail.com Actualització: 19-04-2024 |

||